I want what she has

I read Conversations with Friends

On the way to Casa de Campo I stopped into the EWR bookstore for beach reading, a category I’ve stretched to include quite literally everything under the sun.

On this occasion Conversations with Friends called out to me from the shelf. I like Sally Rooney — at least my sole exposure to her via Intermezzo. I found her latest book to be engrossing in the way listening to your friends’ problems can be, but sans the personal & psychological costs (i.e. the need to respond/express sympathy). This is convenient because offering actual emotional support can be burdensome and often is the opposite of rewarding. Beyond requiring your energy, it strips you naked and exposes you to just how little of your own advice you actually follow.

So yes, that’s what Intermezzo is: it is all the intrigue of psychoanalyzing your friends without the costs. The book is written in such a way that you as the reader are made to feel always like the stable friend lending an ear as the Houellebecqian protagonists, Peter and Ivan, tread water trying to navigate a cruel world. They are marooned in their own existential inertia, unable to act decisively or to confront their own dissatisfaction with the world around them. There’s a grim familiarity to their malaise, a sense that no matter how pitiable they might be, they’re too resigned to seek anything better. I don’t think it’s quite schadenfreude but it’s not far off.

Having read Intermezzo, I opened CWF with certain expectations, mostly about the characters, which turned out to be totally wrong. I found the characters in CWF to be wholly unsympathetic. Frances in particular I would liken to the friend who you constantly waver between wishing you could sympathize with but still can’t and knowing that by doing so you are inadvertently fueling her crippling pathologies. By giving her an ear you are validating what she’s doing as, in some sense, reasonable when it is better seen as uncompromising narcissism.

What is she doing exactly?

Well for starters I should state plainly that Frances knowingly enters into an adulterous relationship with a married man. That’s a tough look. And though it is in theory possible to make all sorts of arguments about the utility of breaking up a loveless marriage, or even that Frances demonstrably helped reinvigorate the marriage, just because we can doesn’t mean we should, and I remain thoroughly unconvinced of ultra new agey luxury beliefs on these types of things. Turns out these arguments would be counterproductive anyhow; more to the point, to absolve her of blame would actually be at odds with what she wants.

And what does she want exactly?

Understanding what Frances wants requires looking beyond what she does in her spare time — that is fuck a married man — to what she says and what she thinks, much like what I do when larping therapist with friends. This is the point at which I paused writing in the hopes of coining a portmanteau for therapist + friend but quickly realized the most phonetically harmonious option was, unfortunately, the one best left unsaid.1

When she’s not busy sleeping with a married man, Frances spends the rest of her time doing God’s work, by which I mean scrutinizing the other characters from a place of detached moral superiority and blinding lack of self awareness. Indeed years later, she still sees her now “friend” and ex-lover Bobbi as some cruel & wicked person for breaking up with her way back when, failing to grasp how blaming others for her own emotional vapidity is the reason why she can’t sustain a meaningful relationship. The worst part is, her reason for wanting a truly deep and intimate relationship is at odds with sustaining one: she wants — no needs — one in order to anchor her value as a person in the world.

Fortunately for us, her narcissism knows no bounds, and she decides that if her place in the world cannot be bolstered by love, she can resort to war. Whereas creation requires contribution, destruction does not. So that’s exactly what she resorts to. She engages in Sherman-like total war.

How does this help her establish her place in the world?

Frances isn’t just destructive; she’s a wannabe victim, a Girardian scapegoat whose actions are governed by a pernicious mimetic desire. For Frances, it’s never enough to simply want something — her desires are defined by what others covet. Bobbi desires Melissa, Melissa desires Nick (or at least what he represents in her own warped telos)2, so Frances’s mission becomes clear: she must make Nick desire her. It’s not even about Nick, or Melissa, or Bobbi for that matter; it’s about Frances climbing to the top of this doomed hierarchy of longing, where the prize is never love or connection but the hollow triumph of being desired. By making herself the center of this triangle of desire, she transforms herself into the axis of destruction, her envy the centrifugal force spinning everyone out of balance.

This works for a while. The problem is this is not a stable equilibrium. It is a web of relationships held together by movement — by chaos — instead of by structure — by order. Since Frances lacks the integration required to sustain a deep relationship, at all times she must push for the escalation of desire which is inherently fleeting. So long as she can keep things unstable in a three-body-problem type of way, she has a place in the world, each escalation of desire fueling the next.

But as is always the case, things eventually become too entropic for even dynamic stability to be an option. In the apotheosis of instability, Frances seizes her final role — arguably what she has wanted all along: to be the ultimate victim, the scapegoat. For the first time, her place in the world is fixed, defined not by her own chaotic longings but by the unanimous agreement of others. She is no longer a fractured, ambiguous figure but a singular, objective fact: the source of all the turmoil. Her expulsion promises resolution for everyone else, and this external clarity is precisely what Frances craves.

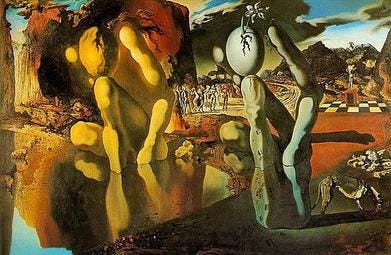

She absorbs the blame, centers herself in their outrage, and transforms their condemnation into a validation of her identity. Through this martyrdom, she convinces herself of her moral superiority while evading any need for internal reconciliation. Victimhood becomes her ultimate currency, the only thing she has left to offer. Like Narcissus gazing into the pool, she admires the beauty of her sacrifice —not for what it redeems but for how it confirms her tragic role. Everything around her fades into the background as she clings to this distorted self-image, fixed at last by the collective agreement of her guilt.

Yet this isn’t an ending for Frances — it’s the next turn in a relentless cycle. Her martyrdom absolves her of introspection for now, but the chaos she thrives on will inevitably rise again. As always, Frances will return to the center of it, spinning everyone around her into disorder until the cycle resets once more.

If you have to ask, don’t, but if you really do take the first two letters of friend and have at it

Resisting the temptation to get sidetracked and write about this :(