I often get this question: why do you work out? There’s a canned answer, the one I’ve become accustomed to giving: mental benefits, I say, the sanity and clarity it unlocks.

This is only partially true, in the sense that I do put significant value in the way working out seems to rewire my brain chemistry for the better. I’m a more emotionally contained person; I can tighten the valve and be okay and not leak onto others.

Two people, on separate occasions this past week, asked me the question, prompting me to reflect on it more deliberately: why do i work out?

I already talked about the first reason—mental benefits—but there’s a more honest one, and the more I’ve reflected the more I believe it to be the primary one. I work out largely for aesthetics. I don’t really care about how much I bench or squat. When someone asks for these numbers, I answer, mostly out of curiosity about their reactions. Surprise? About how much or how little weight? I take both positively, because what I care about is orthogonal. It’s the question that matters.

So what is aesthetics qua telos for working out? In one word it’s beauty. I imagine reading that is as unsatisfying as writing it. What does beauty even mean, especially when it’s so subjective and can vary dramatically across people?

The best approximation I have is a feeling. Something is beautiful when it registers with a deep, profound internal resonance. When it comes to aesthetics being the goal of working out, the meaning of this can look proximally like self-obsession or narcissism in the least charitable first-order determination. This is probably in large part the reason most people don’t admit to it. I like to look in the mirror and like what I see. Is it deeper than that? I don’t know.

I did read something recently that seemed to offer a compelling alternative. Peter Sloterdijk’s interpretation of Rainer Maria Rilke’s poem Archaic Torso of Apollo at least gave me a clearer vocabulary for understanding this aesthetic impulse. He discusses how aesthetics, far from being trivial, can represent a powerful call to ethical self-transformation. So I can claim ethical transformation instead of wanting to look hot? Here is what Sloterdijk says:

You must change your life!' — this is the imperative that exceeds the options of hypothetical and categorical. It is the absolute imperative — the quintessential metanoetic command. [...] The numinous authority of form enjoys the prerogative of being able to tell me 'You must.' It is the authority of a different life in this life. [...] In my most conscious moment, I am affected by the absolute objection to my status quo: my change is the one thing that is necessary.

(Sloterdijk, You Must Change Your Life)

My change is the one thing that is necessary. Okay, that’s dramatic. But maybe it's not all wrong. How does this relate to working out though?

Sloterdijk proceeds to explicitly connect this aesthetic imperative to athleticism, describing how bodily discipline and physical ideals function as tangible, authoritative exemplars:

The authoritative body of the god-athlete has an immediate effect on the viewer through its exemplarity. It too says concisely: ‘You must change your life!’ [...] Give up your attachment to comfortable ways of living—show yourself in the gymnasium (gymnos = ‘naked’), prove that you are not indifferent to the difference between perfect and imperfect [...] admit that you have motives for new endeavors!

(Sloterdijk, You Must Change Your Life)

Ok well this seems dramatic too. Building an ethics around working out feels too hand-wavy when really I could just say I like whatever external validation and other vain rewards come with looking good, the female gaze or whatever. It’s not that deep! To be clear, I don’t see any issue with this and it need not be deeper. But then I ask myself: is this enough to drive the drastic changes I’ve made to and in myself in pursuit of these aesthetic goals?

If I put any stake in this Sloterdijkian call to a deeper internal ethics, answering this question becomes more sensible. For one, it equips me to better think about the akratic’s conundrum.

This is something Agnes Callard explores in her book Aspiration. She describes aspiration as the pursuit of becoming someone who values differently—someone who not only intellectually acknowledges a higher standard but actually reshapes their desires accordingly. Callard highlights akrasia—the phenomenon where we fail to act according to the higher values we recognize—as a natural but challenging part of this aspirational journey.

This is the classic cookie dilemma. If I am someone who cares about my health, why would I eat the cookie, knowingly engaging in something that compromises my goal of improving my health? The answer is I am operating from two intrinsically-conflicting value-perspectives. In other words, I do not have the ability to put both of these options out in front of me like menu items to select from when I’m hungry. In the case of the dishes, I may be looking simply to decide from the value-perspective of asking which of the two items will better satisfy my hunger using taste or pleasure or whatever as proxy. This is not something we have the ability to do when deciding between those other two items—that is eating the cookie or prioritizing our health. These can only be judged from two, mutually-uninhabitable value-perspectives, as if I’m essentially two different people where these value-perspectives “collide,” insofar as such a collision even makes sense to discuss. Callard puts it as follows:

Has the akratic taken the tastiness of the cookie into consideration or not? My claim is that the tastiness of the cookie gives rise to two different rational considerations. One of these—the fact that the cookie will contribute just this much pleasure to my life overall—gets taken into account, and outweighed, in the akratic’s deliberations. The other—the fact that I want something tasty NOW—has not been reckoned in those deliberations. This is because it shows up as a consideration in favor of eating only from a value-perspective that conflicts intrinsically with the one from which she deliberates.

(Callard, Aspiration)

What this means, in effect, is the fact that the cookie is tasty does not pull me back into the deliberation to weight the cookie’s tastiness against my goal to be healthier. Rather it pulls me out of this entire framing, into a value-perspective of simply valuing the cookie’s tastiness. The cookie is TASTY!

As far as how the akratic’s situation relates to the aesthetics of working out, it should follow naturally. Despite fully understanding the imperative to change, to move toward aesthetic self-improvement, I don’t always succeed. Some days the subordinate reasons win out and the value-perspective I take removes me from any such deliberations about the benefits of working out in reaching my aesthetic goals. On other days, the authoritative call Sloterdijk described feels powerful and motivating. This pulling in opposite directions is something I experienced quite often when I first began working out, heavily driven by an aesthetic aspiration, but somewhat distanced from the deeper root-value underpinnings of that aspiration. This is precisely where Rilke’s imperative reappears, now more sharply defined: You must change your life. It is a deep call to action, less intellectualized as part of the deliberations and more this undeniably authoritative call to action. It became not something I merely ought to do but something I must.

It’s tempting to dismiss this interpretation as overly intellectualized or even pretentious—maybe I really do just want to look attractive. But I genuinely feel it is something more. Real, lasting change requires more than vanity; it demands confronting deeper values, and once confronting them, actually changing them.

Conveniently, aesthetics uniquely captures this. It externalizes the ongoing tension between aspiration and akrasia, discipline and desire—making it visible, tangible, real. Sure, my workout routine is partly about physical appearance and mental clarity, but more fundamentally, it’s about continually answering the deeper call for self-transformation. Some days I answer; others I fall short. Yet each day offers a new chance to move closer to the imperative articulated by Sloterdijk, echoed by Callard, and confirmed by my own reflection: You must change your life.

And wow I just sprayed 1,500 words saying what Rilke did in 115:

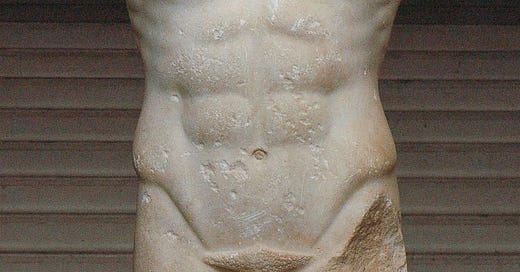

We cannot know his legendary head

with eyes like ripening fruit. And yet his torso

is still suffused with brilliance from inside,

like a lamp, in which his gaze, now turned to low,gleams in all its power. Otherwise

the curved breast could not dazzle you so, nor could

a smile run through the placid hips and thighs

to that dark center where procreation flared.Otherwise this stone would seem defaced

beneath the translucent cascade of the shoulders

and would not glisten like a wild beast’s fur:would not, from all the borders of itself,

burst like a star: for here there is no place

that does not see you. You must change your life.(Rilke, Archaic Torso of Apollo)